Industry Primers

The process of analyzing a company varies considerably from industry to industry. Many industries have their own vocabularies and specific concerns that investors need to consider. This series of articles looks at specific industries and at industry-specific factors that affect investments. The goals are to highlight specific risks, clarify confusing terminology and explain industry-specific metrics for valuation. These methods complement the usual evaluation process, they don’t replace it.

The Oil & Gas Industry

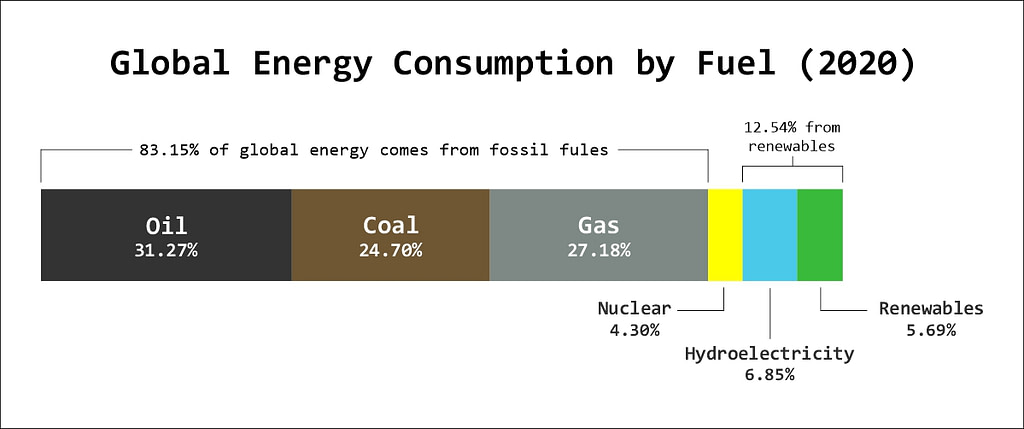

Love it or hate it, the oil and gas sector is a central part of the world economy, powering most of the machines and power plants on Earth. It makes sense for investors to want to have some exposure to the sector that keeps the lights on.

Industry structure

The oil & gas industry is commonly divided into 4 parts:

Upstream: The segment directly involved with drilling and extraction of oil or gas.

The upstream sector is characterized by high volatility. Production costs are relatively constant but the value of the products fluctuates widely with little to no pricing power. The sector is capital intensive and is known for its boom and bust cycles.

Midstream: This segment transports crude or refined material from point A to point B. While midstream often involves pipeline companies, it can also include trains and tankers.

The midstream sector uses very long-lasting assets: a pipeline can stay operational for 30-60 years if well maintained. Investors in this segment will want to focus on buying at a discount, as income is more steady and predictable. Growth is minimal and returns will mostly come from dividends.

Downstream: This segment transforms the raw fossil fuel resources into useful products and distributes them to the final users. This includes refineries turning crude oil into fuel, but also gas liquefaction facilities or the petrochemical industry producing plastic, fertilizers, and other chemicals.

The downstream sector features low margins and is very capital intensive. This sector is most relevant for investors when integrated vertically in a corporation also handling upstream and midstream operations

Services: the O&G sector is a highly technical one. There are many specialized companies providing expertise and tools to the industry. These can be drilling rigs, geological surveys, pipes, valves, pumps, sands, chemicals, and many more

The O&G Upstream Sector

International majors: Large vertically integrated companies operating all over the world.

National giants: Large companies with a monopoly on one country’s resources. Often comes with large state ownership and higher political risk with less emphasis on minority shareholders’ rights.

Small producers and juniors: Usually focused on only one region. Juniors are very speculative, as many are not producing yet and are consuming capital trying to find new deposits.

Measuring Oil&Gas

Oil is usually measured in barrels of oil (bbl) and production in barrels per day (bpd) or million barrels per day (mmbpd). Many deposits contain both oil and gas at the same time. Reserves are then expressed in barrels of oil equivalent (boe) where the gas part is calculated “as if it was oil” to make it more understandable. Many other units are sometimes used, notably cubic feet or cubic meters of gas, metric tons of oil, gallons, or BTU (British thermal units).

Assessing O&G investements

Production costs/Breakeven

Each O&G deposit has a specific geological profile that determines its exploitation costs. While this can fluctuate slightly depending on management’s skills and technology, breakeven costs tend to be somewhat stable due to unchanging geology. To be commercially viable, an O&G deposit’s breakeven costs will need to be at least 30-50% lower than the market price for oil or gas.

The lowest breakeven costs provide a larger margin of safety, as other producers with higher costs will be forced to shut down production first in case of a downturn. This was for example the case of Canadian oil sands in the late 2010s, which were unable to keep producing as oil prices fell. Low breakeven costs also allow a producer to maintain some positive cash flow when the industry as a whole is losing money.

Reserves

Reserves are a key metric for upstream companies. Each O&G deposit has a limited lifespan determined by the resources available in the ground. An oil field producing 100,000 barrels/year with 1.5million barrels in reserves will be depleted in 15 years. This means the current valuation of the company must cover much more than the value of the resources in the ground to produce a profit.

To use the example above, let’s imagine the 1.5m barrels have a breakeven cost of $40. At an expected average of $80/barrel for the next 15 years, this makes 1,500,000 x $40 = $60M of expected profit.

Considering the variability of future oil prices and possible production cost inflation, a solid margin of safety can only be achieved if the company owning this oil field is valued at less than $20M-$30M.

CAPEX, cash flow, and write-downs

The Oil & Gas industry needs heavy and expensive infrastructure and equipment to operate. This makes analyzing O&G financials tricky.

CAPEX is necessary and will always consume a large part of the cash flow generated. The same is true for exploration budgets to find new deposits.

The value of the O&G deposits themselves is an asset on the balance sheet. Together with attached infrastructure, they can be written down in case of long-term low prices, leading to large “paper losses” in earnings but not in cash or cash flow.

For all the reasons above, the preferred metric to value O&G companies has to be Free Cash Flow, instead of earnings, as it reflects better the cost of CAPEX and ignores “paper losses”. It is also important to check that exploration budgets are counted as part of total CAPEX. Without new exploration, the company will run out of resources at some point in the future.

Cyclicality

Launching new O&G exploitations take between 5-10 years, sometimes even more in jurisdictions with high regulatory burdens or for very technical projects like ultra-deepwater drilling or arctic deposits. This is the time it takes to find the oil, get permits, find suppliers, attribute tenders, build the infrastructure, hire, ramp up production, etc.

As a result, new projects tend to be approved only when market conditions seem favorable to future profitability and cash flows are high enough to finance them. So the industry tends to have periods of drastically low investment in CAPEX, followed by a wave of large projects. The consequence is regularly unbalanced production, either too little (after a long period of low CAPEX) or too much (when all the new projects come online at once). This leads to persistent cycles of boom and bust in O&G prices.

Investors in O&G need to consider this risk. Record cash flows and earnings are often a sign of an incoming market top. Alternatively, buying after years of low prices tends to be highly rewarding, even if current cash flows are not that great.

Debt

Due to the capital-intensive nature of the industry, many O&G companies tend to accumulate a lot of debt when launching new projects. This can result in catastrophic failures and bankruptcies in case of a prolongated downturn in oil price. A high-quality balance sheet is a good way to reduce risk when investing in the sector.

Management

The cyclical nature of the industry is an investment concern. Bad management tends to squander profits from good times into growth at the worse part of the cycle. This ends in companies with unprofitable assets and high debt and ends in dramatic shareholders dilution or bankruptcy.

The discipline to raise dividends and improve the balance sheet during good times is a good indicator of management quality. The patience to wait for a downturn to pursue mergers and acquisitions and launch new projects is also a good opportunity to acquire valuable assets on the cheap.

Transportation

Transport bottlenecks can hurt O&G producers’ margins. A good example is Canadian production, which is mostly landlocked and constrained by insufficient pipeline capacity. At times, this can lead to up to a $10-$20 discount on international prices and put a cap on possible growth.

Conclusion

The Oil & Gas industry is a highly cyclical and capital intensive industry. As a result, it’s important to pay close attention to debt & CAPEX, management quality, and the economic cycle. Geography/jurisdiction and geopolitical risks should also be on investors’ checklists. The unpredictable nature of exploration for deposits and the possibility of industrial accidents (for example, the Deep Water Horizon explosion) bring extra levels of incertitude.

Due to these factors, investors in the sector will benefit from higher than usual diversification and should demand a high margin of safety. The O&G industry is more fit for a deep value strategy than for a buy-and-hold portfolio and can bring tremendous returns with an aggressive, well-timed strategy. But it is a risky sector, with very high volatility, and is probably fit only for investors with the right temperament and a disciplined approach to risk.

The post Oil & Gas Industry Primer appeared first on FinMasters.

FinMasters